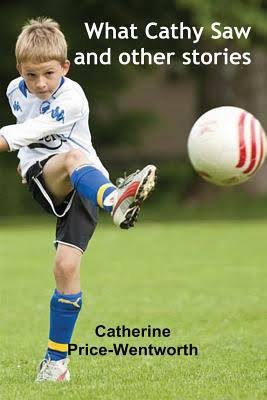

Four short stories about growing up in the twentieth century. About childhood, adolescence and Coming-of Age in an era when friendship was analogue, life was an open book and corporal punishment was a kid’s occupational hazard.

Four short stories about growing up in the twentieth century. About childhood, adolescence and Coming-of Age in an era when friendship was analogue, life was an open book and corporal punishment was a kid’s occupational hazard.

This came up as one of my recommendations on Amazon recently and, after reading the description, I couldn’t resist ordering it. Catherine Price-Wentworth was not listed as the author of any other publications and I half-expected this book, published just last year, to be an amateurish anthology from yet another wannabe writer.

I’m glad I took the risk. It did not disappoint. What Cathy Saw and other stories is a highly original, well-written collection of four whimsical, yet often intense, tales. They’re all different, with distinct narrative voices, set in eras from the 1940s to the 1990s. What draws them together is their evocative depiction of youth — its joys and tribulations and its arcane nature, often shielded from adults who should know better, but seem incapable of knowing.

I love good short stories. The best can pack the punch of a novel into a tenth of the length or less, like a literary espresso. This slim volume (just 90 pages) was just enough to keep me entertained on the train from Leeds to London, but I felt like I’d gorged on a banquet of narration by the time we’d arrived at King’s Cross.

In the title story, a middle-aged woman gently narrates her innocent first love for a boy at primary school, but this turns tables when it becomes an account of their encounter with a pompous, bullying and distinctly dodgy local shopkeeper. Set in 1970s Yorkshire, there are shades here of Billy Elliot and Debbie, Mrs. Wilkinson’s precocious daughter (yes, I know that was County Durham in the 1980s). This story is just as evocative of its place time: as one of Price-Wentworth’s critics observed, “You can almost smell the coal dust.”

Then comes the tale of 13-year-old Nat Turner, a talented aspiring rock musician, and his father Victor, a widower struggling to deal with his son’s emerging independent spirit. Victor thinks Nat’s talent is better suited to the church choir and his attempts to control the boy lead to a run-in between the two and no end of trouble unfolding for poor Nat, who is left with some painfully risky decisions. Told alternately from the perspective of father and son, this is an action-packed roller-coaster of emotion. Hilarious at times, moving at others, its conclusion may bring a tear to the eye but avoids the trap of sentimentality.

Matthew’s Mitzvah tells the story of a young Jewish boy evacuated to a Welsh Catholic boarding school during the second world war. Like the tale before, it focuses on the moral as well as practical dilemmas faced by two of the school’s students after an ill-considered prank goes horribly wrong. Amusingly, the same priest crops up as in the previous story, like a frocked Blackadder, to help resolve the practical and philosophical issues.

The closing short story is another first-person narrative, though this from a 16-year-old boy trying to repair the relationship with his estranged mother. During their meeting, he recalls his loving, liberal upbringing but then uncovers a memory from his infancy when tempers were lost and political correctness fell to pieces…

The characterization throughout is outstanding. I doubt any reader will fail to relate to the young people in the stories as they face the problems and traumas of growing up so familiar to us all. The grownups are well done too, particularly Victor Turner, whose behavior can verge on cruelty, but who still gains our sympathy and understanding.

According to the publisher’s website, Catherine Price-Wentworth (presumably an ad hoc pseudonym for this book) is better known for radio drama and romantic fiction aimed at women. I managed to contact her by email through the publishers to ask her about the background to this collection. She explained that, “I write short stories for my own amusement all the time. These are just four that I felt were worth putting out, but had little prospect of publication elsewhere.”

I see her point. The pieces here certainly push the boundaries of acceptable material for Mills and Boon or The People’s Friend. As the above cover note suggests, there are a few lurid descriptions of school bullying and corporal punishment, which will doubtless appeal to some, but upset others. (Though they may raise eyebrows in the context of modern fiction, they are nonetheless no stronger in essence than those to be found in the works of Roald Dahl or Charles Hamilton.) With some occasional strong language, mild drug references and depictions of under-age drinking and smoking, this is neither a book for prudish old women nor young children.

Though I suspect that anyone else, from teenage to retirement, who enjoys Coming-of-Age stories and appreciates good writing, will be as delighted by this anthology as I was.

You can find the book at Amazon: