Guest article from the owner of Coming of Age Films.com

Bob Balaban‘s Parents is a smart little movie. We know Balaban mostly as an excellent actor (for example from Ken Russell‘s Altered States and Peter Hyams‘ 2010), and here he showed himself as a director with a clear vision and great satirical skill.

A mixture of genres

Parents is a mix between horror, comedy and Coming-of-Age that continues the line of movies from the 1980s portraying American suburbia in not so bright colors, but this time going more to the past – to the 1950s – the “golden age”.

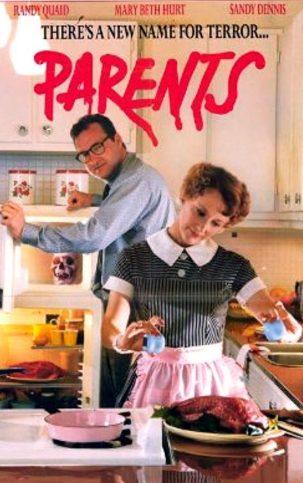

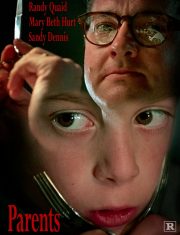

What is this all about? The Laemle family has just moved to a new town – dad Nick (Randy Quaid), mom Lily (Mary Beth Hurt) and son Michael (Bryan Madorsky). The parents can easily navigate in the new environment, but Michael finds it difficult to fit in.

At the same time, he is tortured by horrible nightmares, a thing that has apparently occurred before. Every day, his parents serve meals of barbecue meat (“leftovers from the fridge”, that’s all Michael needs to know, according to his parents). He begins to suspect that the meat is not of the animal variety and that his parents are cannibals.

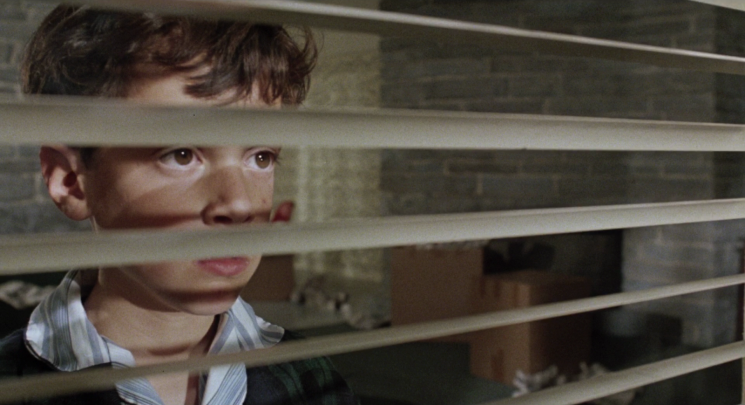

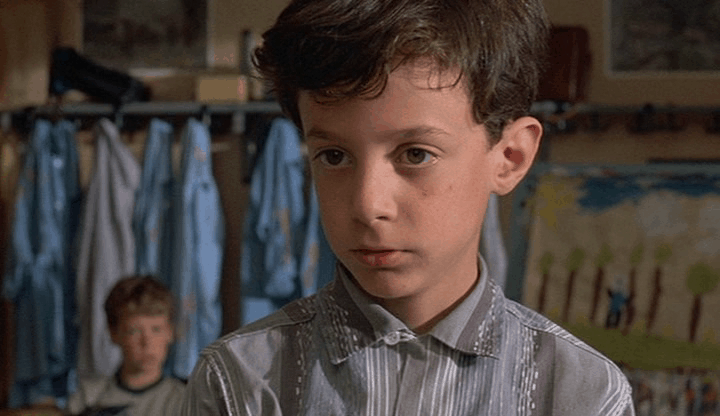

Most of the scenes are shown from Michael’s perspective, he is our guide most of the time. In other scenes, mainly where the film describes the external activities of the family, such as parties with friends and similar activities, Balaban makes fun of the customs and behavior of the people with exaggerated band music, color palettes, costumes and acting. Balaban constantly makes fun of an ‘ordinary middle-class family’. That is apparent from the first minute when they arrive in their new city.

The director also goes below the surface, which is where the real problems are hidden. Michael realizes that his parents and the world around him are not as they seem on the surface. Something is constantly hidden from him by the adults. His parents do strange things behind closed doors and his dad has a job that Michael doesn’t understand.

The director also goes below the surface, which is where the real problems are hidden. Michael realizes that his parents and the world around him are not as they seem on the surface. Something is constantly hidden from him by the adults. His parents do strange things behind closed doors and his dad has a job that Michael doesn’t understand.

Michael’s suspicions are mostly related to the family, the environment in which he spends most of his time. The film is filled with scenes suggesting a heavy Oedipus complex, which is obviously one of the catalysts of Michael’s confusion. The father is the main threat here, but not only in the Freudian sense. He also becomes a very tangible, physical threat.

The theme of exploitation

If we look at the way the director shows Michael’s family and their acquaintances, we will see that there are a lot of rotten things inside them. The world of Parents is the world of exploitation of people – both on the level of nuclear families and on the wider social level, where classes still exist and their invisible and not so invisible borders cannot be crossed. Balaban pictures a world where the middle and upper classes function by the exploitation of the lower classes and of natural resources.

It is a world where its laboratories create toxins (Nick works on the production of a new chemical defoliant) and atomic bombs, a world that experiments on human bodies and souls. But the viewer can see that behind the facades of common-looking houses, in which seemingly happy families live, are hidden crimes of the worst kind and where, with the assistance of other social institutions, the creation of docile and anonymous citizens is taking place.

Cannibalism is a metaphor for all those dark secrets behind the walls of the family, and the metaphor for a more comprehensive social cannibalistic order. Michael realizes very early that the world he has entered is not a happy place on many levels. He’s a child who senses that adults are lying to him, that they are hiding things, and making him accept their rules.

Trailer

One of the themes of the film is the role of leaders and servants within the American 1950’s family, which is a mirror for broader societal norms. Strict, unwritten rules are established within the family and need to be followed. In this case, dad is in charge, mom balances between a husband and a son (she is “converted” by the husband) and the child is the one who needs to accept everything served and continue the family tradition. Older men want to transfer their patterns of behavior, customs and norms to younger persons, not asking them for or wanting their opinions (“We’re bound for life, no matter how much you hate us”). It is a process that happens gradually and it’s expected that Michael will accept it.

Balaban criticizes the authority which parents exhibit over their children, and also any form of social authority. Michael senses that something is rotten here and rebels against it.

There is another, more intimate level of the movie, which clearly connects with the aforementioned level of social criticism. Balaban rightly realizes that the horror genre connects very well with Coming-of-Age motifs, and he is interested in showing the process of growing up with the help of the horror genre tools. Michael is on the brink of puberty and maturation, still not entering that phase, but the process has already begun.

There is another, more intimate level of the movie, which clearly connects with the aforementioned level of social criticism. Balaban rightly realizes that the horror genre connects very well with Coming-of-Age motifs, and he is interested in showing the process of growing up with the help of the horror genre tools. Michael is on the brink of puberty and maturation, still not entering that phase, but the process has already begun.

Therefore, all the elements of cannibalism can be attributed to his wild and troubled imagination, to his changing and sensitive self. That level is present throughout the whole movie and Balaban keeps up the ambiguity until the very end. As is already mentioned, Michael’s Oedipus complex is still not really solved, which adds a lot to the trouble he is experiencing. But it’s clear with whom Balaban’s sympathies lie.

Michael may be experiencing his own inner problems, but something is definitely rotten in his family and he is not making up everything. His changing mind is working on many levels and maybe he’s imagining some things (or perhaps not?), but he may also be seeing stuff other people cannot see. The end of the movie leans more in this direction, still keeping the ambiguity but at the same time making the target of the director’s criticisms clear. The confrontation at the end loses some of the earlier onerous quality of the film, but it’s still a satisfying conclusion to the themes of the movie. The last moments give the film a fitting open ending.

The parallels between this film and Lynch‘s Blue Velvet are obvious. As is the case with Lynch, Parents has several surrealistic scenes where the inner torments of the protagonist come to the fore.

Because he spent most of his career in front of the camera, Balaban’s selection and guidance of all the actors is excellent. Randy Quaid is perfect as the authoritative father, the head of the family that doesn’t like complaints. He is mostly seen from Michael’s perspective – his face is dark and creepy and it seems like darkness will break out at any moment.

Mary Beth Hurt plays a loving mother who wants to help her child to overcome difficulties related to the new environment but shares the views of her husband about Michael’s future. A special revelation is Brian Madorsky, who plays Michael, an eight-year-old who begins to realize that the world is not exactly how he imagined it. There is a mix of confusion, doubt, and fear in his character, and Madorsky is perfect in all the scenes he appears.

Parents is an excellent and unjustly neglected horror-comedy-Coming-of-Age film from a very talented director. It’s an angry little movie with identity, made with love and care from all involved, and it has my highest recommendation.