I first reviewed The Reflecting Skin back in 2007, when TheSkyKid.com was still finding its own identity as a space dedicated to Coming-of-Age cinema. Back then, I dismissed the film’s story as unimpressive and even called the adults “crazy,” like a small-town freak show. I praised the nature shots and young Jeremy Cooper’s performance but completely missed the depth behind Philip Ridley’s haunting debut.

I first reviewed The Reflecting Skin back in 2007, when TheSkyKid.com was still finding its own identity as a space dedicated to Coming-of-Age cinema. Back then, I dismissed the film’s story as unimpressive and even called the adults “crazy,” like a small-town freak show. I praised the nature shots and young Jeremy Cooper’s performance but completely missed the depth behind Philip Ridley’s haunting debut.

In my old notes, I had written: “Nobody behaves like a normal person.” Rereading that line today feels almost naïve — I mistook metaphor for madness.

Eighteen years later, revisiting the film has transformed my perspective entirely. What once felt strange now feels profound — a dark rural fairy tale that the Brothers Grimm might have written before their stories were softened for children. Childhood innocence shatters quietly, and the film’s beauty slowly reveals itself as a mask for decay.

The film opens with a long shot: tiny Seth (Jeremy Cooper) walking through vast wheat fields. His smallness against the horizon establishes the tone — vulnerability from the very start. Ridley’s cinematography tints daylight with bruise-blue melancholy, making it feel haunted, while the saturated fields promise a fragile, almost deceptive pastoral innocence.

The production design adds to this atmosphere: a sofa left outside, teal boards flaking in the wind, candles flickering behind dusty windows. Every object feels lived-in, quietly symbolic, slightly off. Beauty here is always on the verge of collapse.

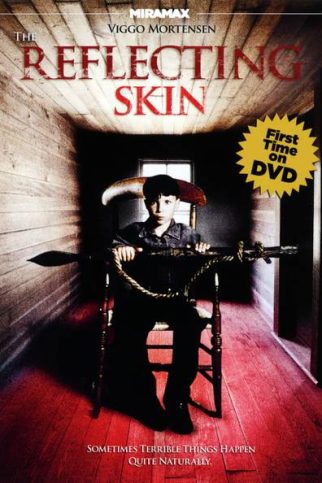

One image remains unforgettable — Seth sitting centered on a chair, a shark’s jaw gaping above him: half halo, half devourer. He is saint and prey all at once. Ridley’s framing often turns domestic spaces into lairs and familiar faces into threats, using static compositions that carry the stillness of a Western before a storm.

The pacing falters slightly past the one-hour mark, mirroring Seth’s emotional unraveling. The slowdown tests patience but also deepens the sense of dread, making the return of tension feel sharper and more intimate.

Jeremy Cooper embodies Seth with remarkable honesty — expressive, luminous, unguarded. His reactions make ordinary sights feel supernatural, the way children perceive the world before logic intrudes. His eyes carry it: wide, glossy, with steady catchlights that make him seem lit from within.

A small lift of the brows, parted lips, and relaxed jaw convey curiosity shading into awe rather than fear. You can see thought flicker across his face — emotion arriving unannounced and unforced. Ridley’s direction trusts him completely; there are no false notes, no exaggerations — only raw instinct.

Some scenes are quietly unsettling. Eye-level shots during Seth’s interactions with adults make the moments intimate and suffocating. The emotional dread builds slowly but relentlessly — you sense tragedy long before it arrives, yet you can’t look away.

At its core, The Reflecting Skin is about innocence corroded by fear and misunderstanding. Beauty lures; wonder conceals danger. The “reflecting skin” becomes both literal and symbolic — a polished surface that hides decay. Through Seth’s eyes, the ordinary world becomes charged with the supernatural, even though what he sees is painfully human.

Loss of innocence here isn’t sudden — it’s gradual, creeping, and inevitable. Howard Blake’s haunting score underlines that journey with tones that sound like a rural lullaby turning into a lament. And that final image lingers — sealing the film’s vision of trauma as a rite of passage.

When I first watched the film, I saw madness where now I see grief. Life since then has offered its own lessons in loss, and perhaps that’s why the story now cuts deeper. After hundreds of Coming-of-Age films, I understand these characters differently. They aren’t “crazy”; they’re broken, trapped, painfully human. The horror was never about monsters from myth — it was about the kind of people who make innocence their prey.

The Reflecting Skin remains unsettling, poetic, and visually breathtaking — a meditation on innocence, fear, and beauty’s deceptive glow.

Readers familiar with TheSkyKid.com will recognize why it resonates so deeply here. The film pushes Coming-of-Age beyond nostalgia, into the darker, more complex territory where wonder and terror coexist.

This isn’t just a film you watch — it’s one you grow into. Eighteen years ago, I saw confusion; now, I see the fragile architecture of innocence and loss. Ridley’s vision hasn’t changed — I have.

See it on the biggest screen you can. Every frame breathes and bleeds. Yet what lingers isn’t the image, but the feeling — that quiet ache of growing up, of realizing that the world’s monsters aren’t always imaginary.