North Macedonian cinema is yet to attract broad international interest. But concerning Coming-of-Age films, at least two deserve to be seen and appreciated by audiences. Svetozar Ristovski’s 2004 film Iluzija and Ivo Trajkov’s Golemata Voda was coincidentally released in the same year.

North Macedonian cinema is yet to attract broad international interest. But concerning Coming-of-Age films, at least two deserve to be seen and appreciated by audiences. Svetozar Ristovski’s 2004 film Iluzija and Ivo Trajkov’s Golemata Voda was coincidentally released in the same year.

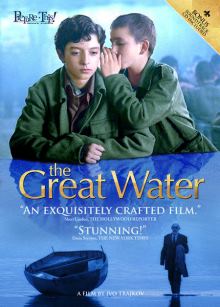

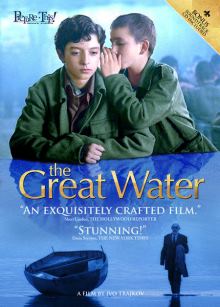

The story in Golemata Voda (The Great Water) revolves around the childhood experiences of a popular Macedonian politician, Lem Nikodinoski, who found himself orphaned in the years following World War II. At twelve years old, he is captured and locked up in a camp (a special orphanage of a kind) alongside other youths who had the misfortune of not only losing their parents in the war but also were considered potential offenders of the ideological ideal set by the Communist Party:

“Children of the Wealthy, the traitors, the collaborators. They had all sorts of names for our dead parents.”

While the story is narrated in the first person by the adult Nikodinoski (as he recalls his childhood in a flashback), it is his younger self from whose perspective the story is told. For many viewers, how a political idea is forced upon and perceived by youth can be intriguing and shocking at the same time. Shocking are the conditions and the attitude towards the children incarcerated in such camps, institutions, and orphanages:

“We were surrounded by wall on all sides. One thousand steps high, two thousand steps wide. A mountain of rack. Damn me, life was so far away from this place.”

Despite the hardships and the ludicrous atmosphere in the camp, love and friendship find a way to bloom like flowers among weeds. Lem meets Isak Keyten, a mysterious older boy (whose role is beguilingly played by a female actress: Maja Stankovska). Isak doesn’t speak much but has a potent presence, self-confidence, and aura that somehow earns him the respect even of the most rigorous disciplinarians in the camp. Little Lem also senses that the new boy is different and, for some unknown reason, he is drawn to him and wants to become his friend:

“I’ve asked myself a thousand times. What was his power? He had something in him. How shall I put it? He radiated with some strange light.”

Yet this mysterious boy does not respond when Lem gathers the courage to ask him if he wants to become his friend. Instead, he gives a simple reply:

“Friendship is to be earned.”

This phrase is what I consider to be the most memorable and vital message that the film presents to its viewers. As the story develops, there are several other values and ideas whose discovery and interpretation, both by the characters and the viewer, resulting in a rewarding experience: what makes people good, which values are important – essential questions that are best addressed in Coming-of-Age narratives such as this one in Golemata Voda.

Isak falls in love with a girl – Lenche Petkova. It’s love at first sight, unfortunately leading to a tragic finale. Lem is jealous of their relationship, of the attention Isak pays to Lenche:

“My nightmare in those days was called Lenche. Lenche Petkova. I kept sticking to them like a leach was as jealous as a young bride.”

In this camp run by fanatics, the disappearance of a pair of red sport shorts causes unthinkable distress. Punishments are administered as the shorts awarded to the headmaster, Comrade Olivera, at a Stalinist competition are described as a religious relic:

“Those shorts are not underpants, comrades. They are not ordinary shorts. They are holy. A sacrament. We bear those shorts in our hearts. They have social, political, and moral meaning.”

The importance given to an object like those shorts is as shocking as how the children are treated, cared for, or educated. Goemata Voda critically addresses the social and political factors that have influenced Macedonian reality after World War II by focusing on the children. With war films featuring young protagonists, an honest, emotional, and poignant portrayal of reality is nearly impossible without associating with or at least having sympathy for, the young heroes.

Having grown up in a country neighboring Macedonia at the end of the social system portrayed in the film, I have seen a lot of movies that are not as critical of Communism as an idea. Many of the Coming-of-Age films released in recent years address the effects of Capitalism over youth in much the same way as Golemata Voda does to Communism. That is why the narrative of this film is best to be considered a portrayal of the time and reality.

One of the best features of this movie is the intriguing mix between realism and mysticism – thanks to the mysterious powers that are attributed to the character of Isak. While I usually prefer dramatic narrative to “stick with the real world”, one has to remember that the world, as looked upon through the eyes of a child, possesses qualities that adults can rarely appreciate.

The entire cast delivers realistic performances, both young and older actors alike. Cinematically, the film doesn’t have any major flaws, and the director even achieves much of the telling of its story through the cast’s facial expressions.

Getting the whole meaning of the film’s ending presents a bit of a challenge. But, overall, I enjoyed the movie and have no hesitation in recommending it. Some of the scenes are rather tough, but both teen and adults viewers may learn much from the story, which once again is something that sets apart films with a Coming-of-Age narrative format — from other film genres.

Golemata Voda Trailer

http://youtu.be/C5Sy7-zDrFg