As a child actor, Mark Lester looked the part. He so looked the part of Oliver Twist that he was cast in the lead role of the 1968 musical film despite having no singing voice to speak of.

As a child actor, Mark Lester looked the part. He so looked the part of Oliver Twist that he was cast in the lead role of the 1968 musical film despite having no singing voice to speak of.

In 2004 the UK’s Mail On Sunday, with Lester’s consent, broke one of the film industry’s hitherto best-kept secrets: his singing parts in Oliver! had been skilfully dubbed by an uncredited Kathe Green, the then 20-year-old daughter of the film’s musical director. Many fans who for years had admired “his” moving soprano renditions of Where is Love? and Who Will Buy? felt cheated by this revelation – but, hey, it was brilliantly done and, after all, what is cinema about if not illusion and suspension of disbelief?

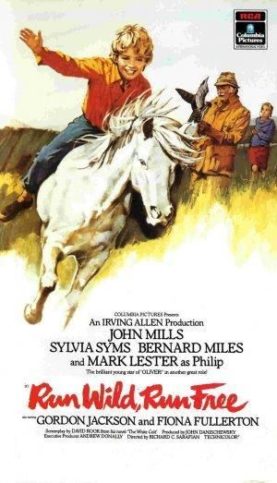

So he couldn’t sing, but Mark Lester was still a talented boy. He moved well on screen and had a face that could tell a thousand stories. In the wake of the commercial and critical success of Oliver! he was a hot property. Within two years, he had starred in no fewer than seven full-length features: Run Wild, Run Free (1969), The Boy Who Stole the Elephant and Eyewitness (1970), Melody, Black Beauty, Whoever Slew Aunty Roo and Night Hair Child (all in 1971).

Only Run Wild, Run Free earned him critical acclaim, which feels cruel with hindsight. It’s hardly surprising that his later performances were lacklustre; one can only cringe at the thought of the pressure the poor kid was under.

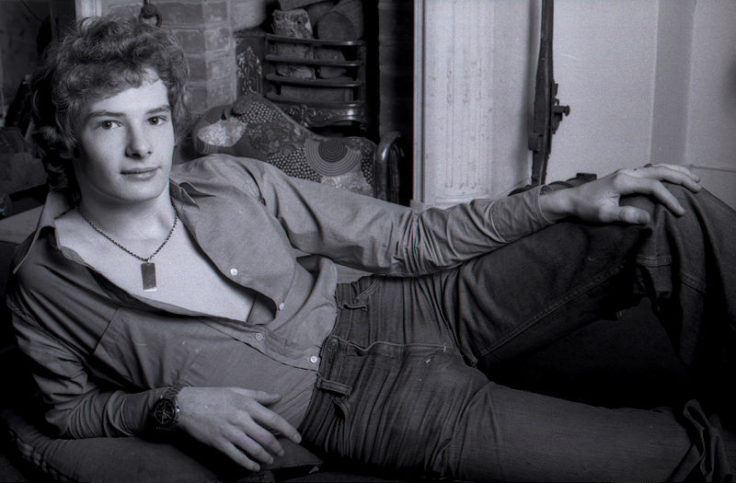

By 1973, the adolescent Mark, now yesterday’s adorable moppet, was finding it hard to get any more good roles. The following few years offered only a series of commercial flops and unkind comments from the critics. He quit acting at 17 and went back to school, which may have been a blessing in disguise. He went on to train as an osteopath and now runs a successful practice in England; a happier outcome than that of his original co-star and close friend Jack Wild, who struggled to cope with the pressure of fame’s limelight and whose career, personal life and health were tragically wrecked by alcoholism.

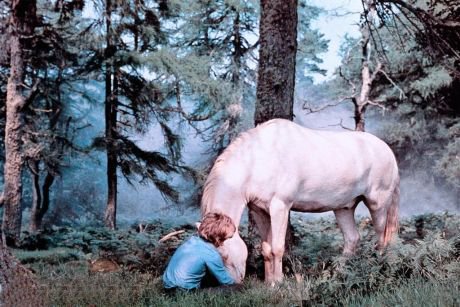

Although Mark Lester’s debut in Oliver! was the pinnacle of his short acting career, his performance in Run Wild, Run Free was by far his best. Based on his novel The White Colt, David Rook’s screenplay tells the tale of ten-year-old Philip. He’s a troubled young soul, both terrified and fascinated by the world around him, who can’t relate to his peers or (least of all) his parents. Indeed, he’s been inexplicably mute (or perhaps just refused to talk) since infancy. No explanation is offered as to why he should be this way, though he would probably have been labelled autistic had the film been made today.

This role could have been made for Lester, whose haunting expression captured the range of a disturbed boy’s confusion, fear, rage and wonderment to perfection.

Philip’s predicament is made worse by his being an only child, with parents (Sylvia Syms and Gordon Jackson) who seem clueless about his needs. They live in an isolated house on a beautiful but sometimes bleak Dartmoor in the south of England. Since he was first able to toddle, the boy has habitually wandered off into the moors and his own inner world, where he seems to take solace in nature.

The nearest neighbour befriends him: a kindly retired colonel played admirably by John Mills.

This older man shares Philip’s love of nature and wildlife and takes the boy under his wing. For the first time, it seems, Philip begins to engage with another person.

Then one day, he sees a wild pony out on the moors. Colt and boy take an immediate shine to each other, and eventually, the pony follows Philip home. Philip names the colt after himself, seeing the shy, solitary, independent animal as a kindred spirit. His condition starts to improve as he tries (in vain) to explain the joy he derives from the pony to his parents.

Tragedy strikes one night during a storm when the pony becomes startled and runs off, not to be found, leaving Philip distraught. Comfort is at hand, though, through another of the colonel’s young friends (this was a more innocent age: there are no sinister overtones to the tale!). Diana is a girl around Philip’s age and the proud owner of “Lady,” a pet falcon. Seeing the boy’s distress, she offers to gift the magnificent bird to him. With the colonel’s help, they train Lady together (no one really owns a falcon!), and a genuinely moving bond develops between the two children.

There are obvious parallels here to a better-known film about another troubled boy whose eyes are opened through falconry, which may be hard to put down to coincidence. Barry Hines’s timeless classic Kes (unquestionably a better film than this one) was released in the same year. But anyone accusing Run Wild, Run Free of being a rip-off should note that David Rook’s novel The White Colt was published in 1967: the year before Hines’s A Kestrel for a Knave.

Diana is played by Fiona Fullerton, who went on to a successful adult acting career. She made a strong debut here. Although her role was less demanding than that of Philip, her portrayal of the girl’s loyalty to and affection for the strange boy is one of the film’s highlights and guaranteed to melt the most cynical of hearts, especially in the climactic scene.

Run Wild, Run Free can’t fail to make an impression with themes and performances like these. It is a memorable film. It’s not, however, a great one. It’s unforgivably formalistic, even for its era. As I’ve mentioned, it’s of the same vintage as the similarly-themed Kes: a gritty, realistic, wholly unsentimental opus. This one uses children and animals to go straight for the viewer’s emotional jugular. It’s brimming with stereotypes: the neurotic, overprotective mother and the emotionally distant, overbearing father (who, naturally, come to learn lessons about themselves as well as their child by the end); the flawed, avuncular adult friend; the young girl whose strength lies in her emerging maternal instinct. And, of course, the disturbed child with hidden depths and abilities. Mark Lester showed such insight into Philip’s condition that I find it a shame he wasn’t given the material to develop the character further.

No spoilers here, but it must be said too that the film’s climax, which uses the heart-wrenching cheat of placing children in mortal danger, is overblown and overplayed. For me, the most powerful thing about it was how young Fiona Fullerton’s performance was left to save the day, though I’m sure that wasn’t the director’s intention.

Not having read the book, I can’t say whether these issues are specific to the film or inherent in the original narrative. Either way, they left the story’s undeniable impact feeling rather hollow for me.

Nonetheless, this is an unforgettable family film that is still apt to capture the hearts of viewers of all ages. Like most of Mark Lester’s post-Oliver movies, it fell into obscurity and for many years was commercially unavailable. Re-released on DVD, it’s now up for a spare change from the major online retailers. I’m glad about that. For all its faults, it’s well worth watching, particularly for the two young stars’ outstanding performances.

Nonetheless, this is an unforgettable family film that is still apt to capture the hearts of viewers of all ages. Like most of Mark Lester’s post-Oliver movies, it fell into obscurity and for many years was commercially unavailable. Re-released on DVD, it’s now up for a spare change from the major online retailers. I’m glad about that. For all its faults, it’s well worth watching, particularly for the two young stars’ outstanding performances.