“Love. It’s very hard to find. But I will love and will be loved.”

http://youtu.be/HI9l63V_mwU

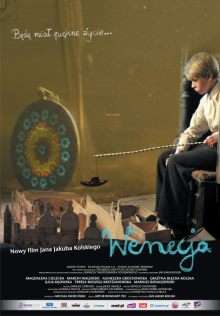

As my interest in European cinema grows, I keep discovering Coming-of-Age films from Eastern Europe that never fail to make a huge impact on me. The 2010 Jan Jakub Kolski film Venice is one of them.

As my interest in European cinema grows, I keep discovering Coming-of-Age films from Eastern Europe that never fail to make a huge impact on me. The 2010 Jan Jakub Kolski film Venice is one of them.

Based on short stories by Wlodzimierz Odojewski, the movie is set in Poland with World War II as its backdrop and tells the story of Marek (Marcin Walewski). Marek is an eleven-year-old boy who, for safety, is sent to the countryside villa of his aunts and female cousins while his father and older brother are summoned to the front.

Early in the film, it becomes clear that Marek and his relatives belong to the privileged class in Poland. He attends a military school, wears fashionable costumes, and his aunt’s villa brings reminisces of a manor. Marek’s parents frequently tour Europe, and thus far, only his age has prevented him from accompanying them on one of their trips to the city of Venice. It’s a city with which he has developed an obsession, thanks to his parents’ stories and what has undoubtedly been his first-class education. When Marek is finally told that he can accompany them on an upcoming trip to Venice, the much-anticipated excursion is put on hold by the outbreak of the war. The boy is not happy at his aunt’s home. Marek doesn’t want to be there but manages to find asylum by building a replica of his dream city in the flooded basement of his aunt’s house.

An encounter with a Nazi officer

I have seen my fair share of Polish Coming-of-Age movies and have found their narratives captivating and appealing. They avoid the meaningless action and over-dramatization that often characterize Western productions and seem to focus on the psychological development and exploration of human nature. Venice uses inner monologues and a stream-of-consciousness style of storytelling, which is especially effective when used in Coming-of-Age stories. This technique allows the audience to get into Marek’s inner world, sense his thoughts and character, and see what motivates, excites, or frightens him. It effectively reflects the disorientation and confusion that Marek feels witnessing the change in his environment and the people he knows imposed on him by the war. He has to make sense of the outside world and the adults surrounding him.

Marek’s relatives

Great direction and storytelling are aided by stunning cinematography. Venice uses an intriguing vintage color scheme that helps establish the period when the action takes place – making the audience aware that what they are about to see has happened in the past. But that’s not all. While viewing the film, its visual style, perspective, focus, and lighting felt familiar to me. I was not surprised to find afterwards that Venice’s director of photography was Arthur Reinhart. Previously, I had loved his work in the 2004 film Jestem (I Am) and the 2011 picture Jutro bedzie lepiej (Tomorrow Will Be Better).

The highly creative camera movements in some scenes boost the artistic value of the movie. A handheld camera portrays a sudden air raid, which interrupts the laid-back pace of the movie – shocking characters and audience alike. In Venice, Arthur Reinhart worked with director Jan Jakub Kolski, who is considered to be the founder of the “magical realism” trend in Polish film-making.

And magical realism is probably the best term by which to describe Venice. A visual poem is another, more clichéd way to describe the film. I don’t hesitate to apply either term to this film because of the beautiful aesthetics in Venice. From them, the viewer will derive much enjoyment and appreciation. The musical themes of Polish pianist Frédéric Chopin provide additional nuances to the visuals, boosting the depth of their emotional impact.

Marcin Walewski as Marek in the 2010 Polish Film Venice

The characters are believable, even though the behavior of Marek’s aunts seemed a bit too weird to me. Some characters could have been better developed, but the lead character of Marek, from whose perspective the story is told, left nothing to be desired. Marcin Walewski portrayed his character’s emotions in a unique and complex manner. At times, he seemed weak, unsure, and common. But at other times, he came across as strong, determined, and aristocratic. An accomplished performance that one would typically expect from an actor with many more years of big-screen experience (before Venice, Marcin had mostly starred in TV productions).

Venice is almost two hours long, and I can honestly state that I truly enjoyed every single minute of it. The story’s overall pace is laid back, with several sudden changes that provide suspense and the desire to know what will happen next. I’m not sure I understood the ending as, while it made sense to me, some of the reviews I have read (like the one written by Dennis Harvey at Variety) suggest that I may have misinterpreted it. I’d love to hear the interpretations of our readers who have viewed Venice. Please comment in the space provided below.

In the end, I don’t hesitate to recommend the film highly. It’s been added to my must-see list for anyone interested in Coming-of-Age cinema, European cinema, or beautiful film-making.

Venice: Official Trailer