The souls of the adult people have shrivelled up. Last year’s rhubarb’s walking the street, Sir.

Timothy Gedge

There seems to have been a golden era of British Television drama in the decade before I was born. I guess it’s swingeing budget cuts that have put an end to that. These days we’re lucky to get more than one outstanding TV movie a year, but back in the 80s the BBC was churning them out on a weekly basis.

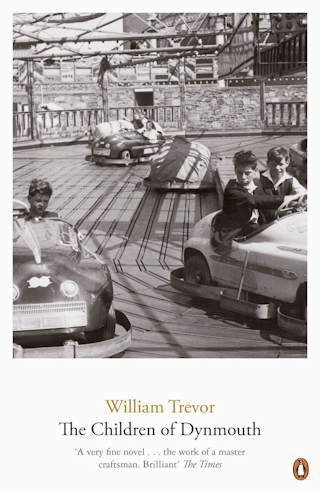

Screen Two was a long-running series of such films. All the ones that I’ve seen were good, many excellent and a few simply stunning. William Trevor‘s screenplay adaptation of his Whitbread Award-winning novel The Children of Dynmouth stands proud in the last category.

Though not a household name, Trevor, who died at the age of 88 last November, was a distinguished Anglo-Irish author, said to have been a candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature. I’ve been a fan of his work since I was a kid and it was a copy of The Children of Dynmouth, which I chanced upon while browsing through my parents’ paperback collection, that introduced me to him.

When I was told that a dramatized version of the novel was available on You Tube, I was skeptical. Trevor’s writing has a distinctive and quite beautiful narrative voice, which inevitably seems to get lost in a screen adaptation. But I was wrong. This may just be the first film made since The Wizard of Oz that’s actually better than the book on which it’s based.

OK, maybe that’s over-hyping what is, after all, a TV movie made on a TV budget. Its creative genes are nevertheless strong: Trevor himself wrote the screenplay; it was directed by the celebrated veteran Peter Hammond (BAFTA Award-winner, noted for such British TV classics as The Avengers, Tales of The Unexpected and Inspector Morse.) The cast features several well-respected names including John Bird, Gary Raymond and a cameo by playwright Peter Jones. Two of the newcomers, Eleanor Tremain and Graham McGrath, went on to have successful acting careers as adults and their promising débuts are documented here. But it was undoubtedly Simon Fox, in his one and only acting role, who stole the show as the main character: 15 year-old Timothy Gedge.

Timothy is a deprived, neglected teenager who spends his days wandering around his small home town spying on people through a pair of binoculars. Few care about him and those who do, like the elderly childless couple the Abigails, live to regret it. As Mrs Abigail herself puts it, “He eats his way into people’s lives – destroys people because he’s been destroyed himself.”

But Timothy can make people laugh – and even though they may often be laughing “at” rather than “with” him, it’s a gift nonetheless. He devises a macabre black comedy sketch for a local spot the talent competition but needs some hard-to-find props. The props are all out there, but he needs to persuade some hostile residents of the town to let him have them, and therein lies the story.

This is a tale of a hapless boy’s blackmail, both literal and emotional, and of half-truths which, when combined with blackmail, can be more insidious than truth or lies alone. Though it has its comic moments, most notably Timothy’s climactic performance in the competition, it’s pretty dark stuff.

If it can be classed as a Coming-of-Age story, then it is one with a twist. For it’s not Timothy who comes of age here: he’s a catalyst who shows no aptitude for learning from experience. His two youngest victims (Tremain and McGrath) learn a few of life’s lessons the hard way at Timothy’s hands, but it’s really middle-aged Mrs Abigail who sees the light in the end during a wonderful showdown with the somewhat inadequate parish priest.

Although he had no prior acting experience, Simon Fox (whose career forked to work behind the camera) was perfectly cast as Timothy. His portrayal of the vulnerable yet manipulative, malicious youngster is creepily realistic and haunted me for days after I watched it. He was, in fact, a young-looking 17 at the time but the maturity with which he handled the role is still remarkable.

Peter Hammond’s direction, with its characteristic use of reflection and shots through opaque screens, suits the story’s themes well. The cinematography here is immaculate and stops short of letting Hammond’s potentially ostentatious techniques spoil the show.

The original score by Paul Lewis, reminiscent at times of Saint-Saëns’ Danse Macabre, fits the film’s mood to a tee and kept me glued to final credits till the end.

Only a handful of the Screen Two productions have been released by the BBC on DVD and (unforgivably, in my view) The Children of Dynmouth is not among them. Indeed, this film has not been aired since its original screening in 1987. Fortunately, a reasonable print of it is up on You Tube, largely thanks to Simon Fox, who supplied the poster with his personal copy of it.

Incidentally, among the Screen Two productions that have been released on DVD is Michael Palin‘s whimsical Coming-of-Age comedy East of Ipswich, which also comes with my recommendation.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1203843/combined