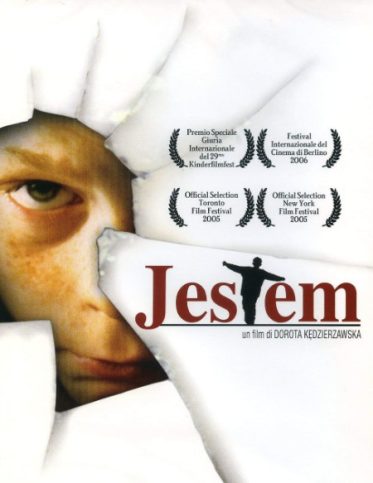

Watching Jestem again, years after my initial viewing, I’m struck not just by the story but by how profoundly it can make one feel a child’s inner life.

Watching Jestem again, years after my initial viewing, I’m struck not just by the story but by how profoundly it can make one feel a child’s inner life.

In 2009, I wrote about this film, marveling at its visual poetry, the warm sepia tones, and Piotr Jagielski’s remarkable presence as the boy. Revisiting it now, I see even more clearly how the director of the film, Dorota Kedzierzawska, doesn’t just show us a boy navigating hardship—she pulls us inside his mind and soul.

From the very first scene, we are plunged into his world: a boy in a reform school, alone, trapped in systems that don’t care. When he escapes and returns to his home, only to find his mother indifferent, the emotional weight of abandonment hits fully. Her words—excuses, half-hearted affection—make us see why he asks the painful question: Who needs me? It’s heartbreaking, yes, but what affects me most as a viewer is understanding how a child comes to such a realization.

You feel the logic of his pain, the quiet accumulation of neglect, and it resonates deeply because Jagielski’s performance is nothing short of extraordinary. Every glance, every subtle twitch of emotion, is a window into a young life forced to reckon with loneliness far beyond its years.

You’re not just watching a boy experience hardship; you’re feeling the architecture of his mind and soul as he navigates neglect, longing, and fleeting moments of care. Every lingering shot, every subtle expression, every quiet musical cue is designed to pull you inside his perspective, so the film doesn’t just tell a story—it invites you to live it. A single look out from a broken window, a silhouette against the river, or the recall of a grandmother’s warmth can convey more than pages of dialogue ever could. Kedzierzawska’s direction, combined with Artur Reinhart’s cinematography, crafts a visual language that is intimate, immediate, and profoundly human.

The film is, of course, a Coming-of-Age story, but unlike more conventional entries in the genre, it doesn’t sentimentalize or soften hardship. It confronts it head-on. The scene where the boy witnesses other children sniffing glue and smoking in a cellar—children who live with their families, unlike him—is particularly striking. It illustrates how survival alone can sharpen a moral and emotional perspective, even in someone so young.

Jagielski’s portrayal of the boy carries the emotional core of the film. The camera often lingers on his face, letting us inhabit his experience directly. In scenes of fleeting kindness—a shared meal, a gentle conversation, a playful moment—his reactions are layered and natural, conveying a sense of self-awareness and yearning that no adult actor could replicate. It’s a testament to both his talent and Kedzierzawska’s skill in guiding young performers.

The supporting elements of the film—the musical score, the precise lighting, the careful pacing—serve not as decoration but as extensions of his inner world. Michael Nyman’s music subtly underscores the emotional currents, never overwhelming, always amplifying. Moments of silence, punctuated by environmental sounds—the river, a distant bell, a scuffing shoe—become part of the storytelling, embedding the viewer even deeper in the boy’s perspective.

Reflecting on my 2009 review, I’m reminded of the visceral reactions the film originally provoked: the sheer empathy for a child whose world is at once precarious and exquisitely observed. Revisiting it now, I am struck by the continuity in Kedzierzawska’s vision, which resonates through her later film, Tomorrow Will Be Better. Both films explore marginalized childhoods, the subtleties of human connection, and the quiet resilience of young protagonists. While Jestem confronts loneliness and neglect, Tomorrow Will Be Better focuses more on hope and adventure—but the through-line is unmistakable: Kedzierzawska immerses us in the emotional truth of childhood, in ways that are cinematic, poetic, and utterly human.

In the end, Jestem leaves one with more than admiration for craft or narrative. It leaves one changed. It reminds us of the fragility and strength of children, the consequences of adult neglect, and the surprising ways even small acts of care can transform a life. Piotr Jagielski’s performance anchors all of this—his boy is unforgettable, not just because of what he endures, but because he makes us feel it, as though we are walking beside him through every step of a difficult, fleeting childhood.

Jestem is a rare film: one that respects the intelligence of its young protagonist, the patience of its audience, and the subtlety of cinema itself. It is a story of survival, of longing, and of the complex architecture of a child’s mind—rendered with precision, empathy, and a profound emotional honesty that lingers long after the credits roll.

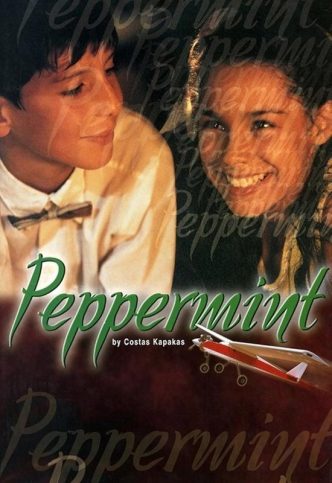

I watched Peppermint, a Greek Coming-of-Age film from 1999, mostly because of the young actor playing Stefanos — Giorgos Gerontidakis. His performance as the 11-year-old Stefanos Karouzos earned him several awards and critical acclaim. He’s expressive, charming, and carries the childhood story beautifully, giving the film much of its emotional weight.

I watched Peppermint, a Greek Coming-of-Age film from 1999, mostly because of the young actor playing Stefanos — Giorgos Gerontidakis. His performance as the 11-year-old Stefanos Karouzos earned him several awards and critical acclaim. He’s expressive, charming, and carries the childhood story beautifully, giving the film much of its emotional weight.

I first

I first

Griffin in Summer is an American independent film that immediately caught my attention. The quirky poster showing a young boy with a peculiar expression hints at a story about a confident, unique kid stepping into adolescence. Going in, I expected an indie Coming-of-Age story with surprises, and the film delivers from the very first moments.

Griffin in Summer is an American independent film that immediately caught my attention. The quirky poster showing a young boy with a peculiar expression hints at a story about a confident, unique kid stepping into adolescence. Going in, I expected an indie Coming-of-Age story with surprises, and the film delivers from the very first moments.

A Father for Charlie is one of those quietly emotional films that stays with you longer than you’d expect. Despite being made for television, this production is of high quality. Its simplicity allows the story and characters to shine, making it a delightful surprise for viewers.

A Father for Charlie is one of those quietly emotional films that stays with you longer than you’d expect. Despite being made for television, this production is of high quality. Its simplicity allows the story and characters to shine, making it a delightful surprise for viewers.

All the actors deliver honest performances, with particular note of the one portraying Walter (Louis Gossett, Jr.) — whose quiet dignity contrasts painfully with the way he’s treated by others.

All the actors deliver honest performances, with particular note of the one portraying Walter (Louis Gossett, Jr.) — whose quiet dignity contrasts painfully with the way he’s treated by others.

Set in the final months of World War II, Secret Delivery, a 2025 Czech film, opens with soft narration and historical texture. Through the voice of a woman recalling her childhood—later revealed to be the sister of one of the central characters—we’re gently introduced to a time when the German Reich still refused to admit defeat, and danger loomed behind every village corner. The film’s tone is observational and restrained, with the camera allowing the viewer to quietly witness rather than directly feel.

Set in the final months of World War II, Secret Delivery, a 2025 Czech film, opens with soft narration and historical texture. Through the voice of a woman recalling her childhood—later revealed to be the sister of one of the central characters—we’re gently introduced to a time when the German Reich still refused to admit defeat, and danger loomed behind every village corner. The film’s tone is observational and restrained, with the camera allowing the viewer to quietly witness rather than directly feel.

I approached

I approached

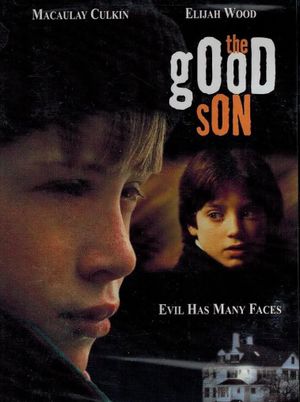

When I first watched The Good Son, my age was not much different than that of one of its protagonists. So many years later, I decided to watch and review it from a different perspective.

When I first watched The Good Son, my age was not much different than that of one of its protagonists. So many years later, I decided to watch and review it from a different perspective.

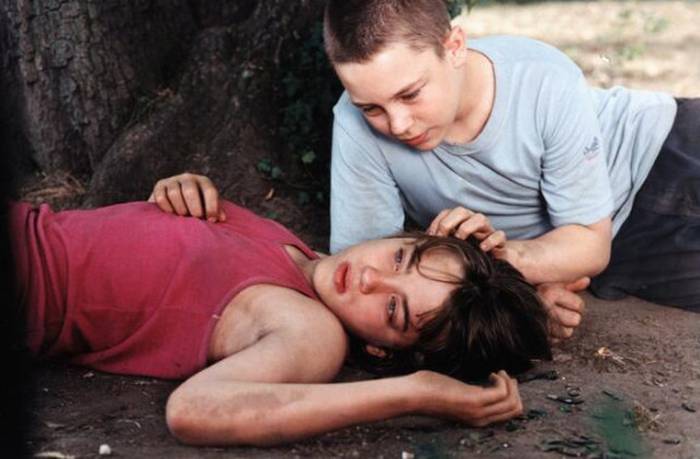

Some films leave an impression. Others leave a scar. The Devils (2002) is the latter. I chose it without knowing exactly what to expect, but from the very first scene, I was completely drawn in.

Some films leave an impression. Others leave a scar. The Devils (2002) is the latter. I chose it without knowing exactly what to expect, but from the very first scene, I was completely drawn in.

I chose Class Trip to view because its synopsis promised a Coming-of-Age story. I knew both

I chose Class Trip to view because its synopsis promised a Coming-of-Age story. I knew both

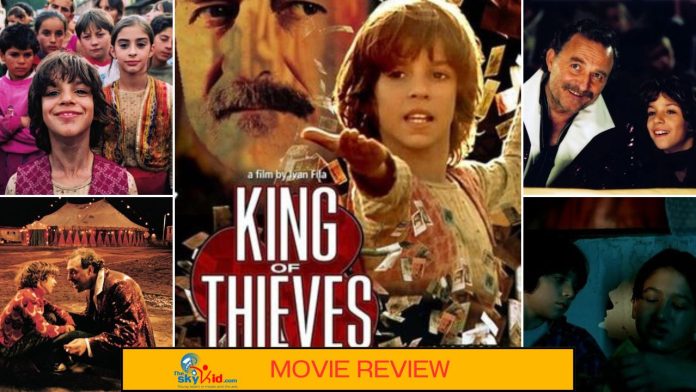

Having been captivated by

Having been captivated by

Can childhood innocence survive the most brutal of betrayals? You will relentlessly ask yourself this question while watching

Can childhood innocence survive the most brutal of betrayals? You will relentlessly ask yourself this question while watching

In Zdenek Jirzsky‘s 2023 film I Don’t Love You Anymore, thirteen-year-olds Marek and Tereza, whose connection begins when Tereza intervenes in a bullying incident involving Marek (an act of pity, she claims, though her true motivations remain ambiguous), form an unlikely friendship and, each haunted by their own personal demons, decide to run away from home together.

In Zdenek Jirzsky‘s 2023 film I Don’t Love You Anymore, thirteen-year-olds Marek and Tereza, whose connection begins when Tereza intervenes in a bullying incident involving Marek (an act of pity, she claims, though her true motivations remain ambiguous), form an unlikely friendship and, each haunted by their own personal demons, decide to run away from home together.